Jews and Chinese Food: Guest Post and Giveaway!featured

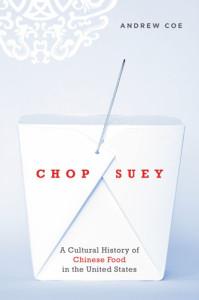

This guest post is by Andrew Coe, author of Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States. In his latest book, Coe unravels the history of the American infatuation with Chinese food, bringing us to San Francisco during the 1848 Gold Rush, New York City in the late 1800s where Bohemians fell in love with chop suey, and along for the epicurean ride in 1972 when President Nixon visited China.

Coe is a wealth of knowledge on the cultural history of Chinese food, a topic near and dear to my heart, and I am fascinated to learn of how my ancestral cuisine evolved over the years in this country. Apparently the Jews of New York played a big part. In this post, Coe delves into the Jewish love affair with Chinese food and how it came to be.

For the record, Andrew Coe is neither Jewish (although his wife is, and he lives in New York City, so that kind of makes him an honorary Jew), nor Chinese (although he scopes out Chinese customers when he eats at Chinese restaurants, and has what they’re having, so that kind of makes him an honorary Asian).

If you like his post, check out his book and learn more about this interesting culinary history. Lick My Spoon is giving away (2) copies of Chop Suey!

To win a copy of this book, leave a comment here telling me: What do you order when you go to a Chinese restaurant (the deliciously cheap, fast service, kind of seedy ones)?

Comments must be submitted by Thursday 7/30, 5 pm PST. Winners will be announced next week on Friday, July 31st.

By Andrew Coe

Jews are sometimes called the “People of the Book” for their devotion to religious study. For American Jews from the 1930s through the 1970s, that book was often a Chinese restaurant menu. On Saturday mornings they went to synagogue; on Sunday evenings they visited the local Chinese eatery to feast on chop suey. Yet many Chinese dishes contained pork and shellfish, foods outlawed by Jewish kosher law. So how did Jews become such devoted fans of Chinese food?

In the New York City of a century ago, Chinatown and the Jewish immigrant Lower East Side lay just a short walk apart. Russian and Eastern European Jews rarely if ever set foot on Mott or Pell Streets. Coming from the cities and shtetls of Europe, most of them practiced Orthodox Judaism. They kept kosher and ate at home where they could be sure that the food was correctly prepared. Eating out in restaurants was an American custom that many had never experienced. Their children, however, often defined themselves more as Americans than Jews. They went to public schools and ate in the dining halls; they found jobs and were invited out for dinner with their co-workers. During the 1920s and 1930s, the favorite places for a cheap yet sophisticated night on the town were Chinese.

To these second generation Jews, Chinese food was cheap, tasty, and sinful–those rosy slices of roast pork and fat and succulent stir-fried shrimp. Maybe if they choked down a cocktail–another new experience–they could get over the guilt of eating non-kosher food. And then there was the décor of cheap lanterns and prints of Chinese maidens on the wall. The Chinese restaurant experience was alien but somehow also welcoming. Unlike in other eateries, the owners did not discriminate; they served white, black, and Native American alike. The Chinese were also strangers in a strange land, like the Jews, and maybe fit in even less. Jews also noticed the many similarities between Jewish and Chinese food, including the use of onions, celery, garlic, and chicken and the lack of dairy products. The bonding of American Jews with Chinese food didn’t take place overnight, but by the 1940s the match had solidified.

However, they still had to get over the kosher problem. Luckily, some anonymous genius invented the concept of “safe treyf.” “Treyf” means “unclean” in kosher law; thus safe treyf means unclean but still okay to eat. When Jews were eating in Chinese restaurants, they applied the rule of safe treyf: if you couldn’t see a dish’s non-kosher ingredients, you could eat it. They wouldn’t order a plate of roast pork, but soup made with pork-flavored stock and chop suey with the pork or shrimp chopped up so small you couldn’t identify it was permissible. And maybe ordering lobster was allowed as well, because it was served by a (non-Christian) Chinese. Flexibility was the key to safe treyf.

In the 1950s and 1960s, American Jews had moved to the suburbs and assimilated into American life. Every Sunday evening, the family went to the local Chinese, where they ordered the family dinner of chop suey, chow mein, and egg foo young with soup and egg rolls. On Long Island, diners at one Chinese eatery were so regular that the owners had permanent name plates made for the booths. For observant Jews, restaurateurs opened kosher-Chinese eateries where the diners could be sure that pork and shellfish were not on the menu.

During the 1970s, when a spate of more authentic Cantonese, Sichuan and Hunan restaurants began to open in cities like New York and San Francisco, Jews were also in the forefront of exploring these new culinary experiences. But then in the 1980s, something happened to Chinese food. The old chop suey joints began to close their doors, while a craze for low-fat, heart-healthy cuisine took hold. American Jews discovered sushi.

Add comment